16th February

2026

The Standing Orders

Proscription of Palestine Action Unlawful

On Friday, the high court ruled the government’s proscription of Palestine Action unlawful. Though the ban remains in place pending the government’s appeal, it represents an embarrassing loss for the government, regardless of the appeal’s outcome.

Palestine Action is a British protest and direct-action group, set up in 2020, which gained prominence in 2024 for its action primarily against the British arms industry, for its complicity in the ongoing genocide in Gaza. In 2025, after vandalising RAF planes by spraying red paint into their engines, having broken into the RAF base Brize Norton, the government proscribed the group in the same way that ISIL, al-Qaeda, Hezbollah, the Wagner group, and the IRA are banned under the 2000 Terrorism Act. Indeed, the government passed the proscription as part of a package which banned the violent terrorist Maniac Murder Cult, and the neo-Nazi Christian ultranationalist Russian Imperial Movement. Under the act, membership of and expression of support for proscribed groups is illegal and punishable by up to ten years imprisonment.

In response, large demonstrations were held in London. Since the proscription, the Metropolitan Police has arrested about 2500 protesters, including 532 in one day, the highest total in 24 hours in the last ten years. Almost all of these arrests were for peaceful demonstration, as tame as holding placards with the words: “I oppose genocide. I support Palestine Action.”

Critics remonstrated what they saw as an outrageous incursion on freedom of speech and assembly, a view vindicated this week by the high court. On two grounds, the court found the ban unlawful: that the secretary of state had not followed her own policy on the use of the Terrorism Act, and that the proscription was disproportionate and therefore an impermissible imposition on the rights to protest afforded by the European Convention on Human Rights. The Terrorism Act states, “the Secretary of State may exercise his power under subsection (3)(a) [proscription] in respect of an organisation only if he believes that it is concerned in terrorism [emphasis added],” and then goes on to outline what it means by “concerned in terrorism.” Policy then describes the more detailed means of determination as to whether a proscription would be proportionate and is legally required. Meanwhile, the 1998 Human Rights Act allows the UK high court to consider the compatibility of legislation with the ECHR, without making claimants go all the way to Strasbourg. The UK has parliamentary supremacy, meaning that the judiciary cannot override parliament in its sovereign legislative functions, but the amendment proscribing Palestine Action was a ‘statutory instrument’, not an act of parliament, and is subject to restrictions, and can be struck down if ultra vires, that is, ‘beyond the power’ or scope conferred by whichever act grants the power used to implement this statutory instrument in the first place. Hence the ruling.

Shabana Mahmood, the home secretary, has expressed the government’s intention to appeal the ruling. If the decision is upheld, the proscription will be quashed; until then, support for the group remains a criminal offence, and while the Met Police have announced they will not arrest suspects until the appeal is concluded, they will still be collecting evidence of support, which will be actionable retrospectively into this period. Let’s hope they won’t get a chance to (for the sake of the general fundamental rights to free expression and to peacefully protest, not the sake of the proscribed group). What a waste of police resources! And what a win for the ECHR!

(Once again, a win for fundamental freedoms, that is.)

Thai Constitution No. 13

On Sunday last week, Thailand held its third general election since its most recent coup, with a strong showing from the pro-junta governing party and a disappointing result for the disadvantaged reformers.

Thailand has had at least eleven coups since the 1932 coup that saw the end of the absolute monarchy and a transition to constitutional rule. The two most recent, in 2006 and 2014 respectively, bear many similarities. Both resulted in the removal of an embattled prime minister following a period of political crisis, the dissolution of the government, the dissolution and abolition of the Thai senate (the upper house of the Thai legislature), the repeal of the constitution, the establishment of a military junta (the euphemistically named Council for National Security and National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO)), the implementation of an interim constitution, and the eventual implementation of a nominally more democratic constitution a couple of years later. No constitution since has approached in adherence to democratic principles the constitution enacted in 1997 suspended in 2006.

In both cases, the king, Bhumibol Adulyadej, the third longest-reigning monarch of any sovereign nation, who ruled from 1946 to 2016, legitimised the juntas, with all but explicit endorsement. The monarchy has held significant esteem in Thailand, particularly Adulyadej, given his long reign, though has faced mounting opposition in the 21st century. (His son, Vajiralongkorn, is a far more divisive figure, described by The Economist as “widely loathed and feared” and by Asia Sentinel as “erratic and virtually incapable of ruling”, and has been completely unable to reach the stature his father achieved. He restored the position of Royal Noble Consort for his mistress half his age, whom he fell out with and imprisoned for a time, and had his dog elevated by the Royal Thai Air Force to the rank of Air Chief Marshal.) After both coups, and in general, the vague Thai lese-majeste laws, which criminalise criticism of the monarchy, and which have been described as "possibly the strictest criminal-defamation law anywhere," have been vigorously implemented by the juntas, to protect themselves from criticism, and to punish dissenters in general, republicans naturally leaning rather anti-junta.

After the last general election in 2023, the Move Forward Party, a progressive democratic reformist party, won the most seats in the lower house and attempted to form a government with the centre-right populist Pheu Thai, but was brazenly blocked by the unelected pro-junta senate, reaching only 324 of the 375 votes required of the whole legislature. So Pheu Thai went into government with conservative populist Bhumjaithai with the conspicuous support of the Palang Pracharath Party (PPP), the party of the NCPO.

In 2024 and then 2025, the notorious Constitutional Court removed both the first and second Pheu Thai prime ministers, and dissolved the Move Forward Party, citing a 2021 ruling that equated calls to reform the monarchy to effort to overthrow it, and therefore unconstitutional. The court, which was re-formed from the constitutional tribunal instituted by the NCPO, is seen by many observers as one of the principle means by which the royalist and militarist factions can influence politics without overt action, or significant elected representation. Indeed, the Move Forward Party was in fact the second incarnation of the Future Forward Party, dismantled by court order in 2020.

In exchange for an election within four months, the People’s Party (PP, formerly MFP formerly FFP) agreed to support a minority Bhumjaithai caretaker administration. The PP had been polling favourably and hoped to improve on their previous election win, but it wasn’t to be.

Though they won the party list ballot by a reasonable margin, their constituency support failed to materialise strongly enough outside of Bangkok to overcome the rather consolidated royalist vote for Bhumjaithai, and they took 108 seats the Bhumjaithai’s 193. Pheu Thai receded to third place with 74, as the new Kla Tham Party, a splinter group of the PPP, surged to 58 seats. Meanwhile the PPP collapsed to just 5 seats, and the ultra-conservative nationalist United Thai Nation Party collapsed to 2, the two parties losing 69 seats between them.

In the broader context of the ongoing border dispute with Cambodia, the staunch nationalist views of the prime minister, Anutin Charnvirakul, may have helped secure his party’s grip on the conservative royalists, while significant party resources and support from local rural figures helped in the areas the PP struggled to reach. In contrast to the Bhumjaithai’s simple non-descript nationalism and not much else, the PP was unable to capture the narrative with a singular push for reform, unable to campaign on change to the lese-majeste laws, and without the spectre of the prime minister at the 2023 election, a general who had helped lead the 2014 coup.

Also on Sunday, a referendum on the drafting of a new constitution passed with about two votes in favour to one against. If the drafting process is not so protracted as to effectively kill the proposal, the constitution would be the thirteenth since the first in 1932. A constitution for each coup, then (depending on how you count the coups). Still, there is plenty of room to improve on the military authored 2017 constitution, and the result shows an appetite for change. Such an appetite will surely grow again.

Election Results: Bhumjaithai: 193 (+122) seats (18.1% party list vote); PP: 118 (-33) seats (29.7%); Pheu Thai: 74 (-67) seats (15.63%); Kla Tham: 58 (+58) seats (1.84%); Democrats: 22 (-3) seats (11.1%); Thai Ruamphalang: 6 (+4) seats (0.46%); Prachachat: 5 (-4) seats (1.22%); PPP: 5 (-35) seats (0.40%); Economic Party: 3 (+3) seats (3.17%); United Thai Nation: 2 (-34) seats (2.14%); Pheu Chart Thai: 2 (+2) seats (1.91%); Thai Sang Thai: 2 (-4) seats (0.56%); Others: 10 (-9) seats (10.75%); None of the above (3.06%) (+1.79pp).

Bangladesh Will Reform Their Constitution Too

On Thursday, Bangladesh held its first election since the overthrow of the fifteen-year-long Hasina regime.

Characterised by significant democratic backsliding, the previous election being only partly free and not fair, the Hasina regime toppled following the July Revolution in 2024. What began as student protests over the civil service’s quota system, which allocated less than half of places to candidates by merit alone, allotting the majority of the rest to descendants (the children and grandchildren) of combatants in the 1971 Bangladesh War of Independence, developed quickly due to widespread dissatisfaction, a ten-day internet blackout, and then the murder of over one thousand protestors, mostly students, and including children, by police on government orders. By early August, Hasina had resigned and fled to India, where she remains, since sentenced to death in absentia by the (domestic) Bangladeshi court, the International Crimes Tribunal.

A technocratic interim government followed, in an attempt to return stability before the reimplementation of a democratic system, which culminated this week in these elections. The Bangladeshi electoral system is essentially UK-style first-past-the-post, though fifty seats in the national legislature are reserved for women, and are filled proportionally according to the directly elected members of the legislature. As a result, they are just as disproportional to actual vote shares. So, a two-party race emerged, between the big-tent Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), and the conservative Islamist Bangladesh Islamic Congress (Jamaat-e-Islami, BJI). Though the BNP has had its own controversies with political violence, it has strongly marketed itself as the sensible unity choice following years of turmoil, a view shared by voters, who returned the BNP to parliament with 211 of 300 elected seats. Their platform managed to attract rural working-class voters while retaining its traditional affluent urban support, leading support by young people and in particular young women, faced with an alternative which aims to bring about (democratically) a sharia-law based state.

Perhaps in response to their lack of support on these issues, the BJI have moderated views on women’s rights and have more clearly articulated support for the rights to work and dress freely, but still largely reject women in positions of power within the party and out. It was clearly not convincing enough as they came in a distant second with 68 seats. Their electoral group won a slightly improved 77 to the BNP+’s 214, while independents won 7 and a non-affiliated Islamist party won 1.

As well as a general election, a referendum was held to significantly amend the Bangladeshi constitution, which passed with a strong 68% of the vote. Among other things, it will establish an upper chamber to their legislature, term limits for the prime minister, codify the right to protect private personal information, require the support of leaders of the opposition for a declaration of a state of emergency, and prevent the restriction of fundamental freedoms during such a state. It will also abolish the country’s incredibly strict prohibition on floor crossing under which MPs who voted against their party’s position automatically forfeited their seats, a rule that has prevented motions of no-confidence in the prime minister and has consolidated power in the select few at the top of government. The change should bolster the power of the legislature and improve accountability. Both major parties supported the revisions.

Election Results: BNP+: 214 seats (BNP: 211 seats; Gono Odhikar Parishad: 1 seat; Ganosanhati Andolan: 1 seat; Bangladesh Jatiya Party: 1 seat); 11 parties: 77 seats (BJI: 68 seats; National Citizen Party: 6 seats; Bangladesh Khelafat Majlis: 2 seats; Khelafat Majlis: 1 seat); Islami Andolan Bangladesh: 1 seat; Independents: 7 seats. One seat is acant pending a by-election due to candidate death.

Massive Swings in Special Elections: The Democratic Path to Congress, Part I

Because this is a static site, you might need to clear the website's cache for the graph to format correctly: you can do so with CTRL+F5

The Trump effect on elections outside the US has been pronounced. Without the convicted felon in office, the centre-left Liberal Party may not have won in Canada, nor the centre-left Labor Party in Australia, both having faced mountains to climb to defeat once-favourites for the premierships, Pierre Poilievre and Peter Dutton. Both were maligned as Trumps-lite, and that narrative proved their undoing. While Dutton pulled down his whole coalition, the Canadian Conservatives made gains in 2025, and despite this, Poilievre lost his seat! (A fawning Conservative lackey has since vacated his safest-of-safe Albertan riding to allow Poilievre back into the house. At least Dutton, who also lost his seat, graciously resigned as party leader.) Without Trump’s outspoken desire to annex Greenland, Danish prime minister Mette Frederiksen faced going into the Danish general election, which must be held by November, with deteriorating polling, but instead saw her fortunes change on a dime, and has tripled her party’s lead over their nearest competitors to +9 percentage points in the last month and a half.

It looks like such an effect might be coming to haunt Trump closer to home. In the 2025 November elections, Democrats flipped 25 out of 118 Republican held seats, while the Republicans flipped none. Democrats returned a supermajority to the New Jersey house, while breaking supermajorities in two red-state senates. They outperformed Harris by an average of 13 percentage points, a result, which if replicated in November, will make open R+4 to R+6 seats competitive and EVEN to R+3 seats competitive, even against incumbents. (Because the conventional partisan index measures deviation from the average district, the Democrats need an improvement of 1 percentage point on their 2024 performance to be statistical favourites for EVEN seats. The current 50-50 seat is D+1.) In particular, despite the enormity of the Republican treasure troves, they will be spread thin, as campaigns up and down the country gobble up all the kind billionaires’ money. It is also the type of swing which could nullify the effects of the Texan mid-decade redistricting. The Texan delegation to the house of representatives is currently composed of 25 Republicans and 13 Democrats, of whom two come from districts formerly EVEN and R+2, according to the 2025 Cook PVI. In their eagerness to disenfranchise, the newest Republican gerrymander seized on inroads made by Republicans (just Trump really) in the Hispanic community in Texas, which swung towards Trump compared to 2020. But with Trump’s approval among Hispanic voters at all-time lows given his indiscriminate (as to citizenship and immigration status) discriminate (as to race) mass deportation efforts, such a ploy could backfire spectacularly, the Hispanic population of Texas being as large as it is. Taking the 2024 elections alone, the redistricting would return 30 Republicans to 8 Democrats, the five most competitive Republican seats being long shot but not unfeasible R+4, R+4, R+5, R+7, R+7. Using what may turn out to be a more reasonable estimate of vote preferences in 2026, a composite of results from 2020 to 2024, the ninth to thirteenth best seats for Democrats swing to the eminently targetable D+2, R+1, R+3, R+4, R+5. Redistricting in other red states poses issues for Democrats, who would be expected to lose somewhere between seven and sixteen seats due to redistricting, though the retaliatory redistricting in California and Virginia, along with moves to follow suit in other blue states could cancel out 3 to 14 of these losses. It's all up in the air.

More recently, special elections in Texas and Louisiana have recorded incredible swings of 31 and 37 points away from Trump towards Democrats. Though special elections are usually unrepresentative and in both cases above, low turnout affairs, such enormous swings simply cannot be explained away by low-information voters staying at home. Indeed, Republicans in congress are worried by these results, which suggest a more substantial realignment away from the voter coalition than delivered Trump to the white house for a second time, with Republican legislators collateral damage. US voters can generally be relied upon to vote according to national politics and the presidency, usually against them, in the midterms in normal times, and these are not normal times for US politics.

Needing only three gains to take control of the house of representatives, a Democratic gain looks to be somewhat of a foregone conclusion. (That is, unless the Supreme Court finally do as they clearly would like and kill what’s left of the Voting Rights Act. If done before June, the move would catalyse a frenzy among southern states to carve up their majority-minority districts, and dilute safe Democratic black-majority seats among the surrounding safe Republican white-majority seats. The 1965 act is used to ensure minority racial groups are provided the ability to choose the representative they would like. To do so, one needs to gerrymander of course, but this has long been seen as uncontroversial, by most as a necessary evil to ensure the voting power of minorities is not disappeared by white-majority state legislatures.)

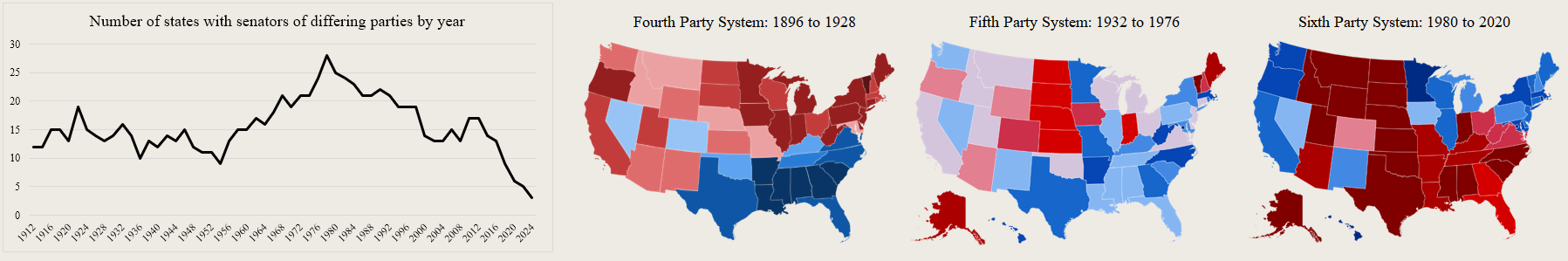

But what about the senate? The senate poses a far greater issue for Democrats long-term. Political partisanship is at a 100-year high: just three states have senators of different caucuses (that is, counting the two independent senators as Democrats, given they caucus with them). The graph below shows the number of states with opposed senators each congress since the ratification of the seventeenth amendment, which mandated that senators be elected directly, rather than by their state’s legislature. I think this is a good measure of partisanship; a high number of split-party states either represents a simultaneous willingness to vote for either party or an openness to switching party in the two or four years between consecutive senate elections.

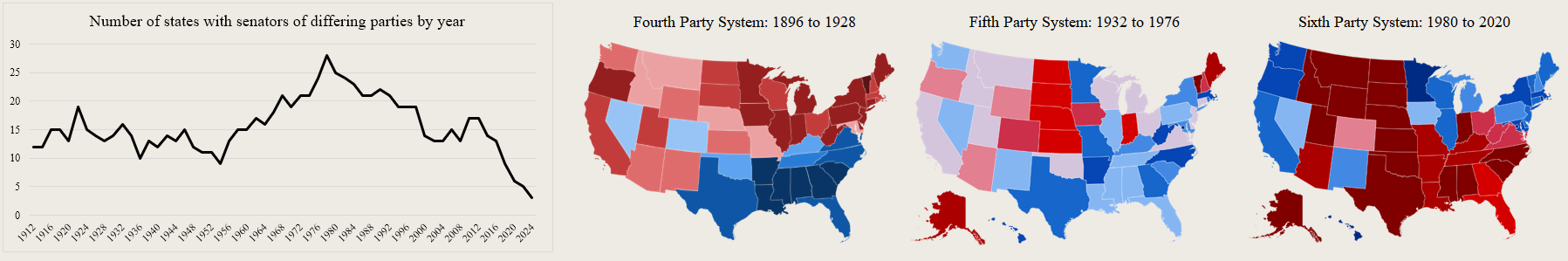

Credit: via Wikimedia Commons, Will Be Continued:

Fourth Party System; via Wikimedia Commons,

Mad Mismagius:

Fifth Party System,

Sixth Party System.

As you can see, three is a catastrophic collapse from the highs of the 70s and 80s. Part of this is likely due to the gradual switch in party positions and geographical dominance: during the third, fourth, and fifth party systems from the 1860s to the 1980s, the Democrats (in blue) were the party of the American South, and were the party for slavery during the third system and white supremacy in the third system in particular. Now of course, in the sixth (or seventh) party system, they are the party of the North. The following maps, which aggregate presidential election results, give an indication of the magnitude of this switch.

The current understanding of state party-allegiance is of twenty-four Republican states, seven swing-states, and nineteen Democratic states. The Democratic states have 37 Democratic senators and 1 Republican; since the 2024 elections, the Republican states are a 48-senator clean sweep; and the Democrats have a strong lead in the swing states with 10 blue to 4 red. Despite this clear advantage, they are of course in the minority, with only 47 in total. If the Democrats do manage a federal trifecta (and kill the filibuster), statehood for DC, which has no voting representation in congress, should be top priority, especially given the district’s strong desire for it. Referenda in Puerto Rico are far less clear cut on support for statehood, and with Trump out of the picture, PR would probably redden from blue to purple, but it seems likely that PR will become a state at some point, and they should certainly be given the choice. But even then, Democrats would face difficulty in taking the senate and instead need to find wins in red states.

But how? I do not think it is a coincidence that the most recent increase in partisanship correlates with increasing access to the internet. One consequence is that the Democratic party is far more homogeneous than it once was. The debate as to candidate selection is often reduced to national-scale moderate vs progressive or old guard vs young blood terms, and both sides of each have had strong wins in the last year (Mamdani in New York for young progressives; Spanberger and Sherrill in Virginia and New Jersey for the moderates). It makes more sense to identify which democrats have the best chance to win in each state, and where this consideration needs to be made. In a state like New York, where Democratic victory is all but guaranteed, all power to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, standard-bearer for the progressive left, if she decides to challenge senate minority leader Chuck Schumer for the Democratic nomination in 2028. She has a very good chance of usurping him (and I hope she does). But she couldn’t win in Texas.

So, where are Democrats targeting in 2026? Find out next week!